Algospeak, or internet euphemisms that are used to get around social medias’ algorithms that ban certain words, have picked up attention. But are euphemisms used on the internet for other reasons?

Panini. Seggs. Auti$m. You’ve probably seen some of these internet euphemisms as you scroll social media. A new trend on social media, termed “algospeak,” has people using a certain type of euphemistic language to get around social media word bans or algorithms. People have also incorporated this internet language on sites without strict bans, like Twitter.

Merriam-Webster defines a euphemism as “the substitution of an agreeable or inoffensive expression for one that may offend or suggest something unpleasant.” Avoidant language can protect, keeping hard or offensive language away from those not ready for or comfortable with it. But the same language can also be manipulative, getting around bans or reframing words to make them seem less harmful.

This manipulative language, algospeak, often has bad intentions and, in such cases, should be avoided according to internet etiquette. But does that mean all euphemisms should be avoided online? Are there other reasons for using euphemism besides protection and manipulation?

Let’s take a look at a case of when euphemism is used with additional intentions to help us understand how to react to euphemistic language and use it ourselves. My two data sources—the news and Twitter—had no algorithms to manipulate, so the intentions of writers can help us see why else people use euphemistic language.

COVID-19 Algospeak and Euphemisms Online

A lot of algospeak was generated during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, some social media sites put informational labels and banners on posts with words such as “pandemic,” “COVID-19,” or “vaccine.” TikTok even banned posts completely based on pandemic-centered language.

The pop-ups and bans were meant to stop misinformation, but many people were annoyed with their overuse. To get around them, people started using euphemistic language to get their pandemic-related point across. One of the most prevalent words used was “panini” and other pan- words.

The Case of Pandemic Euphemisms in the News

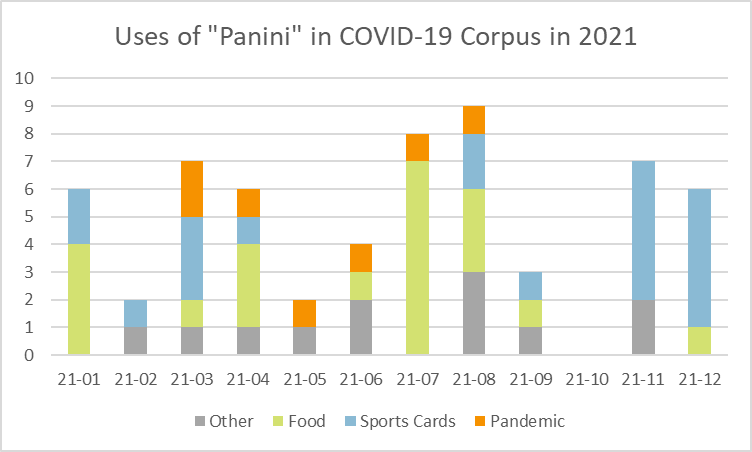

To gain an initial sense of how frequently “panini” was used in popular discourse, I looked to see how frequently it appeared in the news. I searched for the word “panini” in the Coronavirus corpus, a corpus made from news texts published from 2020 to 2022. Despite the fact that all the texts in the corpus explicitly mention COVID-19 or the pandemic in the title or at least twice in the body text, not all instances of “panini” in the corpus were made in reference to the pandemic, so I analyzed each one to make sure, categorizing each by their referent (other, food, baseball card, pandemic). Data about the occurrences of each category can be found in the graphic below.

Some of the additional uses of the word “panini” came from references to the food, like a local newspaper’s reference to a restaurant’s menu including a panini: “For lunch there are soups and salads, hot and cold sandwiches, including a Cuban panini and Vernona burger.” Additional instances reference the sports card company called Panini: “Carpenter said that he is hoping his one-of-a-kind, signed Tom Brady Panini XR football card will one day cover the college tuition for his son Matthew.” Instances that didn’t fit into any of these categories were sorted as “other,” like references to Lil Nas X’s song called Panini.

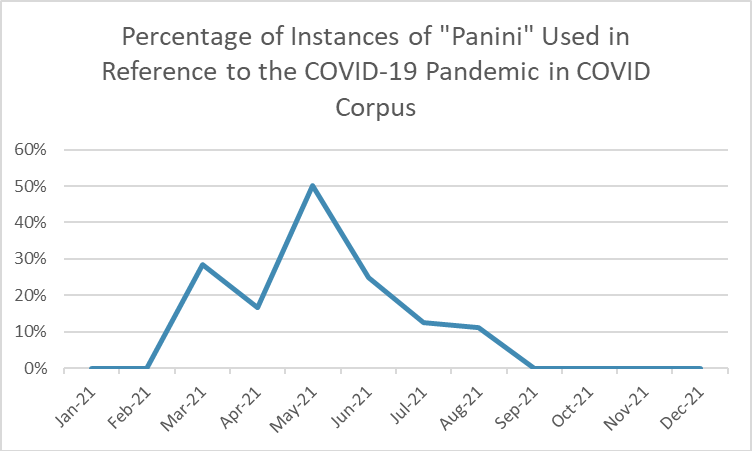

The first use of “panini” in reference to the pandemic appears in March of 2021. Though it is never used more than twice in a month in reference to the pandemic, “panini” is used in reference to the pandemic at least once for the next six months, peaking proportionally in May 2021 where half the occurrences refer to the pandemic, as seen in the graphics below

With this frequency data, I next set out to analyze the writers’ intentions for using panini in the news. On these news sites within the corpus, there wasn’t an algorithm to get around, so the algospeak wasn’t manipulative. But the corpus’s context showed that the euphemism “panini” was frequently used along with the word “pandemic,” so writers probably weren’t attempting to protect people from the language it substituted for. So if it was neither manipulative nor protective, there had to be a third reason for the euphemism.

What I found is that in the corpus, many of the “panini” instances that referenced the pandemic were explanatory in nature (four out of the seven). For example, NPR wrote, “You don’t even need to say ‘pandemic’; any multisyllabic word or phrase that starts with P will work. So you ge [sic], like, ‘They’re out here going to a party in a Panini Press?!’”

Though few, instances of “panini” as a euphemism made their way to news sites during the COVID-19 pandemic. Their context shows them used neither to protect nor manipulate, suggesting that euphemisms can be used online for a third reason—to explain.

The Case of Pandemic Euphemisms on Twitter

From here, I studied another site with no algorithm bans—Twitter—to see if there were additional reasons people used the euphemism panini online. A random selection1 of tweets from the first half of 2020 shows #panini used in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic as early as June 2020.

The writers’ intentions on Twitter seem to be different than intentions on both other social media sites and news sites. Many of these posts use the words pandemic or COVID, clearly not avoiding the words altogether. They were included in tweets about wearing masks, comics surrounding the lockdown, and more. Some of these tweets used it together with #COVID or even #pandemic, clearly not attempting to avoid a ban or pop-up.

What I found is that many tweets used the term as an inside joke or parody. Because of the humorous nature of the tweets—combined with the use of the words “panini” substitutes for—it seems writers were attempting to use euphemism to create humor. Some examples include jokes about unreasonable regulations and metalinguistic jokes about the euphemism itself. These examples illustrate a fourth reason for using euphemisms online—for the sake of humor.

So what?

It seems that the algospeak trend was picked up as something other than a way to manipulate an algorithm or to avoid language. Once it moved from stricter sites to less strict sites and all the way into more formal edited language like within the corpus, it was neither manipulative or protective. It was just new language, used with new intentions. The Coronavirus corpus indicated that news articles use euphemisms that began as algospeak to explain social phenomena. And #panini on Twitter was used more as an inside joke.

Because there are many reasons for internet euphemisms, we can best understand them based on their context and the reasons people are using them. So when you are deciding whether to use a euphemism or not or when you see others using euphemisms, look at the motivation and the context to determine whether the euphemism follows internet etiquette or not. On sites with algorithm-based bans, euphemisms may be seen as more manipulative. On news sites, euphemisms seem acceptable in explanations. And on social media sites without algorithm-based bans, euphemisms may help create humor on your page.

–Isabel Tueller

Methodology Note

1I used Twitter’s search function to find tweets with the hashtag #panini from each month from January 2020 to February 2020. I reviewed the first page of results for each search, categorizing each as food related, baseball card related, pandemic related or other.

FEATURE IMAGE BY sqaurefrog

Learn More

https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/04/08/algospeak-tiktok-le-dollar-bean/